My tracking mount is now in the shop, so I thought I’d have to go without taking astrophotos for a while … but when I woke up early yesterday morning, my husband recommended I go outside and check out the conjunction of the crescent Moon, Venus, and the star Regulus. It was beautiful!

I got my old setup – my trusty Canon 60D and tripod and intervalometer/cable release and set up to take some pictures.

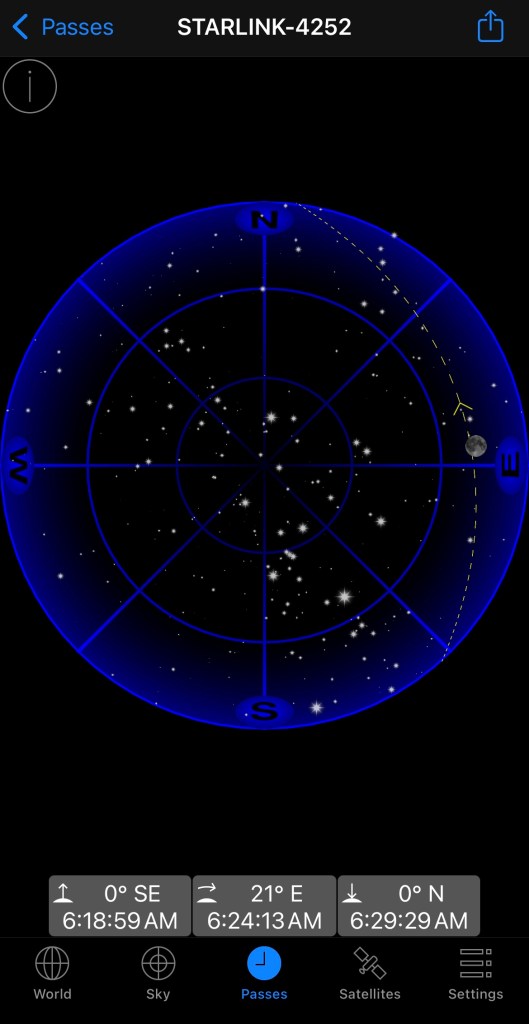

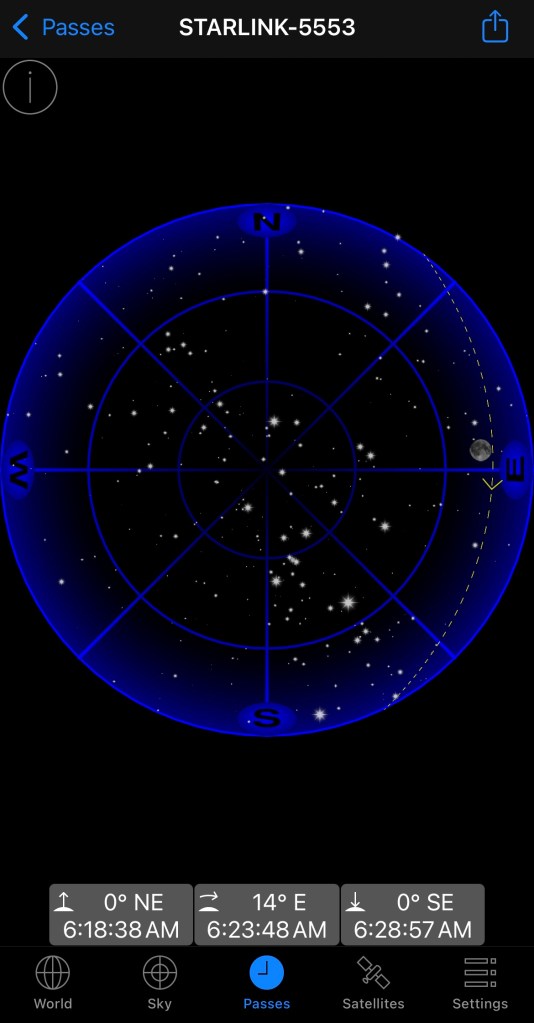

As I was focusing on the Moon and looking at camera view screen, I saw a satellite moving across the dark face of the Moon! How cool! Then I saw a second satellite moving across the dark face of the Moon in the same direction, which made me suspect I was seeing Starlink satellites.

I processed the best image I took in PixInsight and discovered there was a bright spot on the face of the Moon. So I used the GoSatWatch app on my phone, set to 0 degrees horizon and no limit on magnitude to get all the satellites, and figured out which satellites crossed the face of the Moon when my picture was taken. There were a ton of Starlinks which made them the very high probability source. My time stamps are only good to the minute, and I don’t have the exact time the Starlinks crossed the moon although when they were high in the East was a good stand-in, but it looks like there were two potential Starlinks crossing the Moon around the time of my photo!

It was a pretty neat thing to see, and I think it would be fun to try to capture a bigger satellite (eg the International Space Station) crossing the Moon with my telescope after I get my tracking mount back. Something to look forward to!

Camera geek info:

- Canon EOS 60D in manual mode set at f/4, 1/60 second exposure, ISO 1250

- Canon EF 70-200mm f/4L USM lens, set at 200 mm, manual focus on lunar craters

- Tripod

- Intervalometer used as cable release