In late March 2025, a new comet, C/2025 F2, was found in imagery from the Solar Wind Anisotropies (SWAN) camera on the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO).

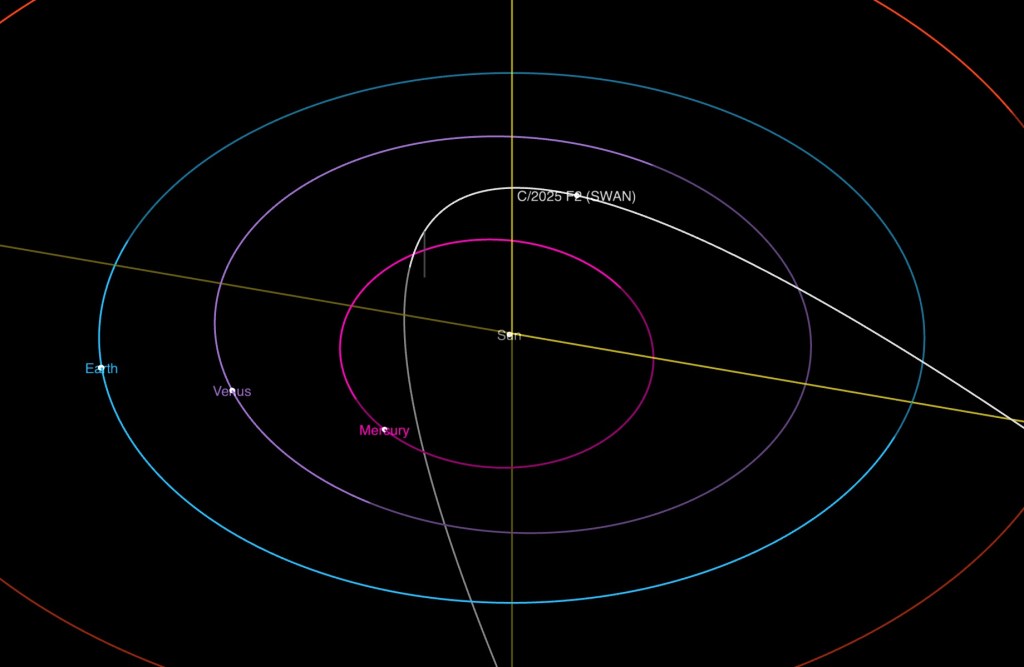

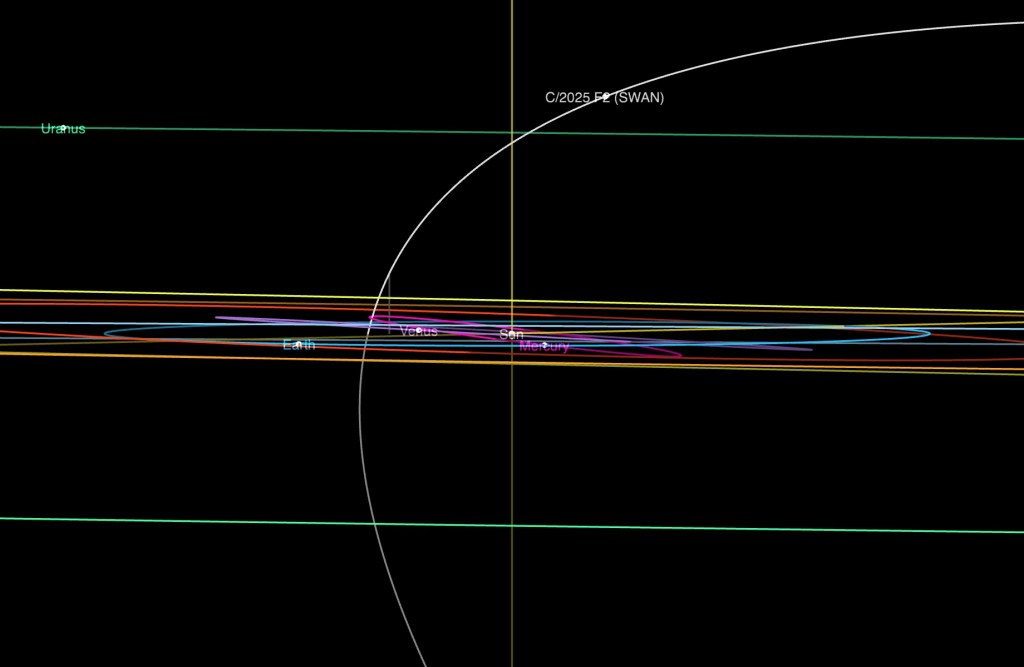

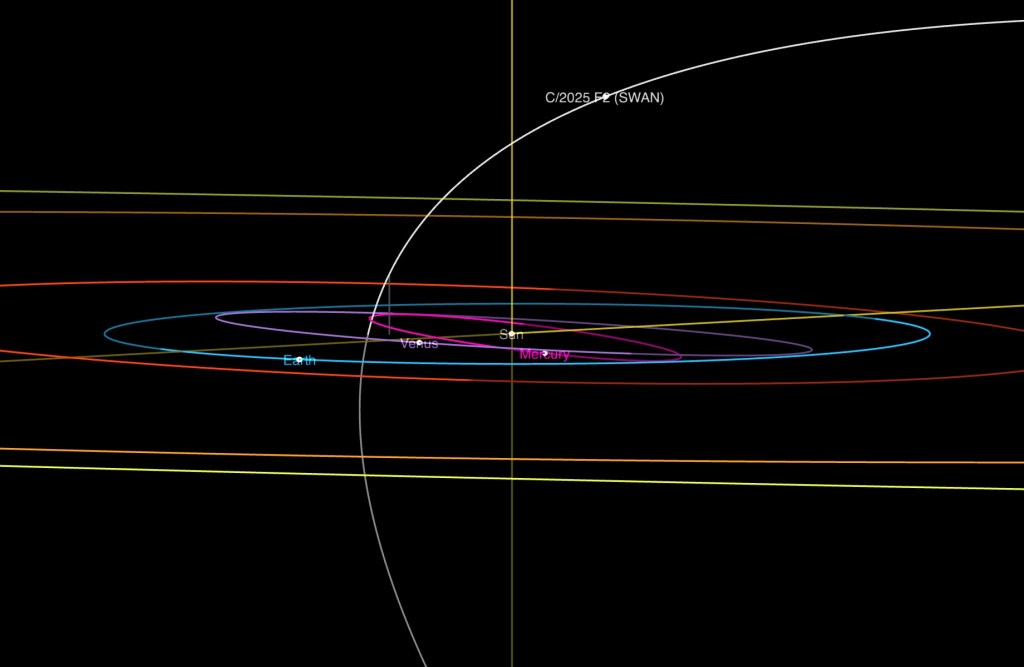

Orbit images Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) has a great orbital dynamics viewer where you can see its orbit relative to the planets. It’s quite fun to play with! C/2025 F2’s orbit is very parabolic and nearly 90 degrees out of the ecliptic plane. It is coming in from north of the ecliptic plane, will loop around the sun near Mercury’s orbit on May 1, 2025, and then head back out to the outer solar system south of the ecliptic plane. So it’s visible from the Northern Hemisphere in the early morning now, but as it approaches the sun, it will get more and more difficult to spot, and it will be more visible from the Southern Hemisphere on its outgoing trajectory.

“Now” was the best time to see it from the Northern Hemisphere, and we have had a nice string of days with clear skies, so last weekend, it was time to go comet hunting!

I used the JPL Horizons System to predict the comet location and motion so that I knew where to point my telescope and I knew how long the images could be without “smearing” the comet – 15 seconds for my telescope and camera combo.

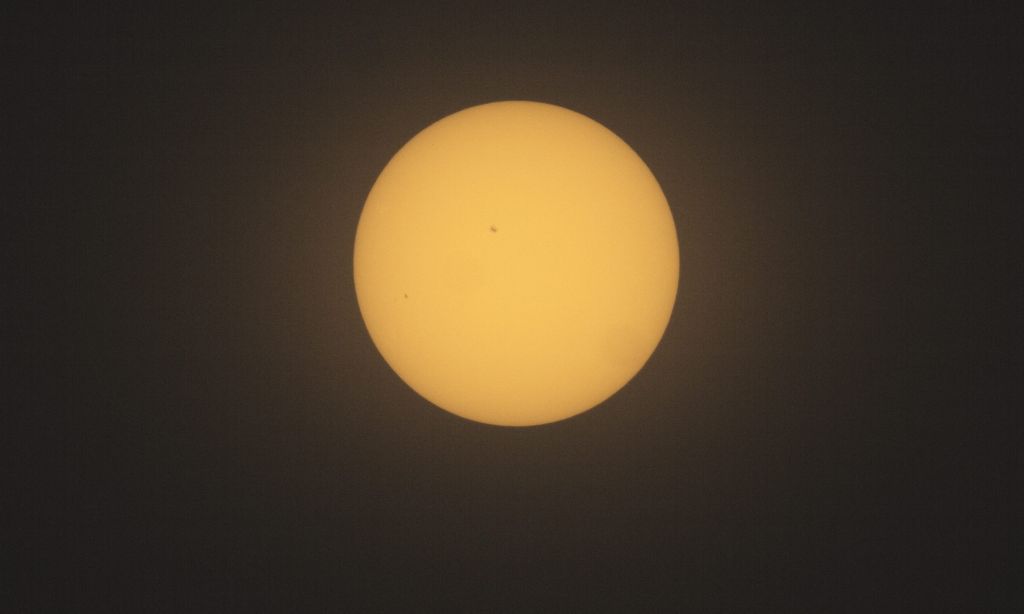

I loaded up my gear, and my husband and I drove to our favorite early morning comet viewing site in Bacliff, Texas. By the time I had everything set up, the comet was above the horizon. My preprogrammed location contained a small, fuzzy object which looked like a comet on the first try! I was really delighted that everything worked on the first try; this has not always been the case in the past. I spent some (probably too much) time trying to get it positioned better in the frame and started imaging. It was brighter in green than in red and blue which, with its fuzziness, confirmed to me that it was likely a comet. I couldn’t see a tail in my single images.

I set up my regular camera to see if I could get some wider field images. Given what I ended up with in the telescope images, I do not think the comet will be visible in the wider field images.

Both my husband and I tried to find the comet with binoculars, with no luck at all.

We finished the morning with a lovely sunrise and breakfast.

Processing comets is still a big challenge for me, with more steps than processing a nebula. I mostly follow the excellent process outlined by Adam Block in his Comet Academy. Blinking through my frames, I could see the comet moving across the sky, another sure indicator that I had captured the right object! After aligning, integrating, and stretching the comet images, I could see a faint tail that stretched all the way across the field of view (about 2 degrees with this telescope and camera combination), but the background noise was brighter than it was. I tried several methods to make the tail visible, and the one that worked the best was to “murder the background” as Adam says in one of his videos.

I’m probably not going to get another chance to capture this one, but I enjoyed getting to see it at least once. Has anyone else tried to go out and capture this one?

Camera geek info:

- William Optics Zenith Star 73 III APO telescope

- William Optics Flat 73A

- ZWO 2” Electronic Filter Wheel

- Antila RGB filters

- ZWO ASI183MM-Pro-Mono camera

- William Optics Uniguide 32MM F/3.75

- ZWO ASI220MM-mini

- ZWO ASiair Plus

- iOptron CEM40

- Bacliff, Texas Bortle 6 suburban skies

Frames:

- April 12, 2025

- 47 15 second Gain 150 Green lights

- 30 0.02 second Gain 150 Green flats

- 45 15 second Gain 150 Blue lights

- 30 0.02 second Gain 150 Blue flats

- 50 15 second Gain 150 Red lights

- 30 0.05 second Gain 150 Red flats

- 30 Flat Darks from library

- 30 Darks

Processing geek info:

- PixInsight

- BlurXterminator

- NoiseXterminator

- StarXTerminator

- Generalized Hyperbolic Stretch