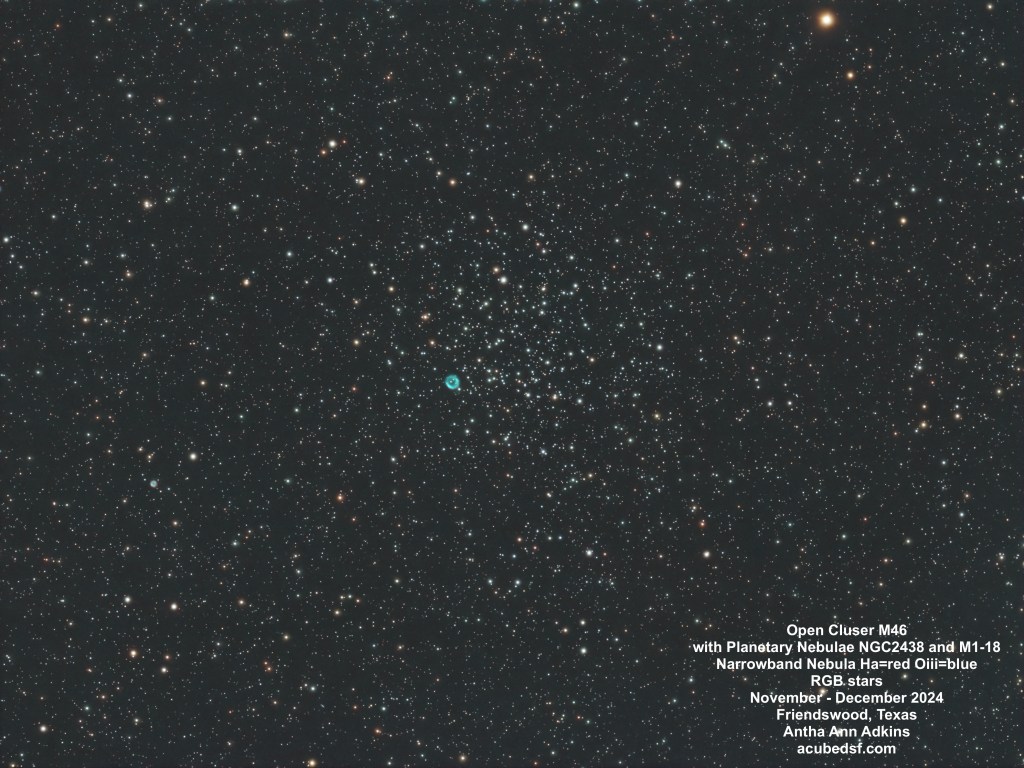

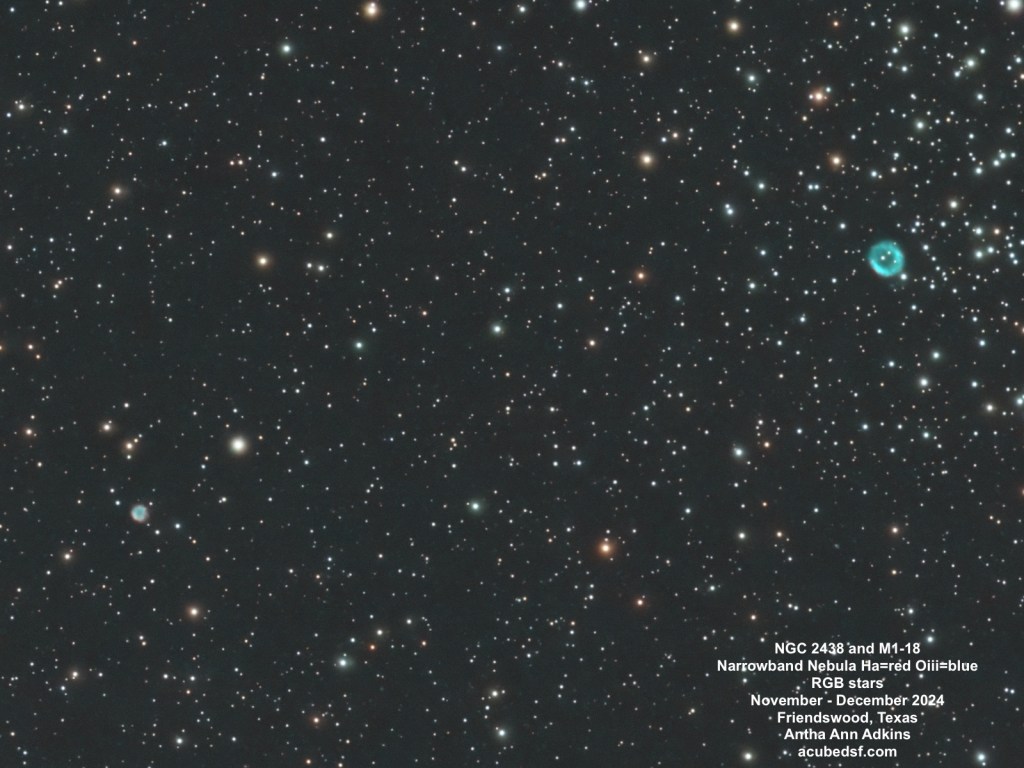

Sh2-274 or Abell 21 or the Medusa Nebula is a planetary nebula – the gases expelled from a red giant star before it becomes a white dwarf, lit up by that star. It’s located in the Milky Way, approximately 1930 light years away, and it has an apparent size of 10.25 arcminutes, making it 5.75 light years across. Given the amount of time it would take to reach that size, it is considered to be an “ancient” planetary nebula.

I find these small nebulae beautiful and fascinating. Each has its own unique structure. This one has a Ha rim and an Oiii interior and has filaments (the filaments are probably the source of its nickname, the Medusa nebula).

In this image, the stars came from images using red-green-blue filters, and the nebula came from images using Hydrogen alpha (mapped to red) and Oxygen iii (mapped to blue) filters. The nebula was processed separately from the stars to maximally enhance it.

I had hoped to get enough data on this one the last time we enjoyed the dark skies in Dell City, Texas, but there were a lot of high clouds that limited the amount of data I collected there. So I collected more data from my driveway at home until I had almost 7 hours of Ha data and 6.7 hours of Oiii data.

Camera geek info – Narrowband:

- William Optics Zenith Star 73 III APO telescope

- William Optics Flat 73A

- ZWO 2” Electronic Filter Wheel

- Antila HO and RGB filters

- ZWO ASI183MM-Pro-Mono camera

- ZWO ASiair Plus

- iOptron CEM40

- Friendswood, Texas Bortle 7-8 suburban skies

- Dell City, Texas Bortle 2-3 dark skies

Frames:

- January 24, 2025

- 14 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- February 15, 2025

- 100 30 second Gain 150 Red lights

- 30 0.05 second Gain 150 Red flats

- 98 30 second Gain 150 Green lights

- 30 0.02 second Gain 150 Green flats

- 60 30 second Gain 150 Blue lights

- 30 0.02 second Gain 150 Blue flats

- February 20, 2025

- 19 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- 5 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- February 21, 2025

- 68 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- 30 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- February 22, 2025

- 48 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- 32 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- April 7, 2025

- 131 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- April 8, 2025

- 130 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- April 10, 2025

- 72 60 second Gain 150 Oiii lights

- 30 0.2 second Gain 150 Oiii flats

- April 11, 2025

- 133 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- April 12, 2025

- 137 60 second Gain 150 Ha lights

- 30 0.5 second Gain 150 Ha flats

- 30 Flat Darks from library

- 30 Darks from library

Processing geek info:

- PixInsight

- BlurXterminator

- NoiseXterminator

- StarXTerminator

- NBColourMapper

- Generalized Hyperbolic Stretch